Vault Over

Vault Over attraversa spazi temporali e geografici, mitici e mitologici e ci conduce con il proprio sguardo all’interno di un esercito di terra schierato.

Vault Over crosses temporal, geographycal, mythical and mythological spaces and leads its sight into an earthernwa- re army deployed.

Cristina Gori

PREMESSA

Nei secoli il mondo cambia, la storia è tale in quanto trascorsa, passata e in qualche senso perduta. Ma chi si occupa davvero di storia non ama dire che il passato è perduto, ma che è sepolto, nel senso meno tetro del termine: semplicemente coperto. Il mondo cambia, infatti, ma non si trasforma davve- ro. Il suo è un lavoro di sovrapposizione e di stratificazione. Il mondo invecchia e, invecchiando, si copre di qualcosa di nuovo.

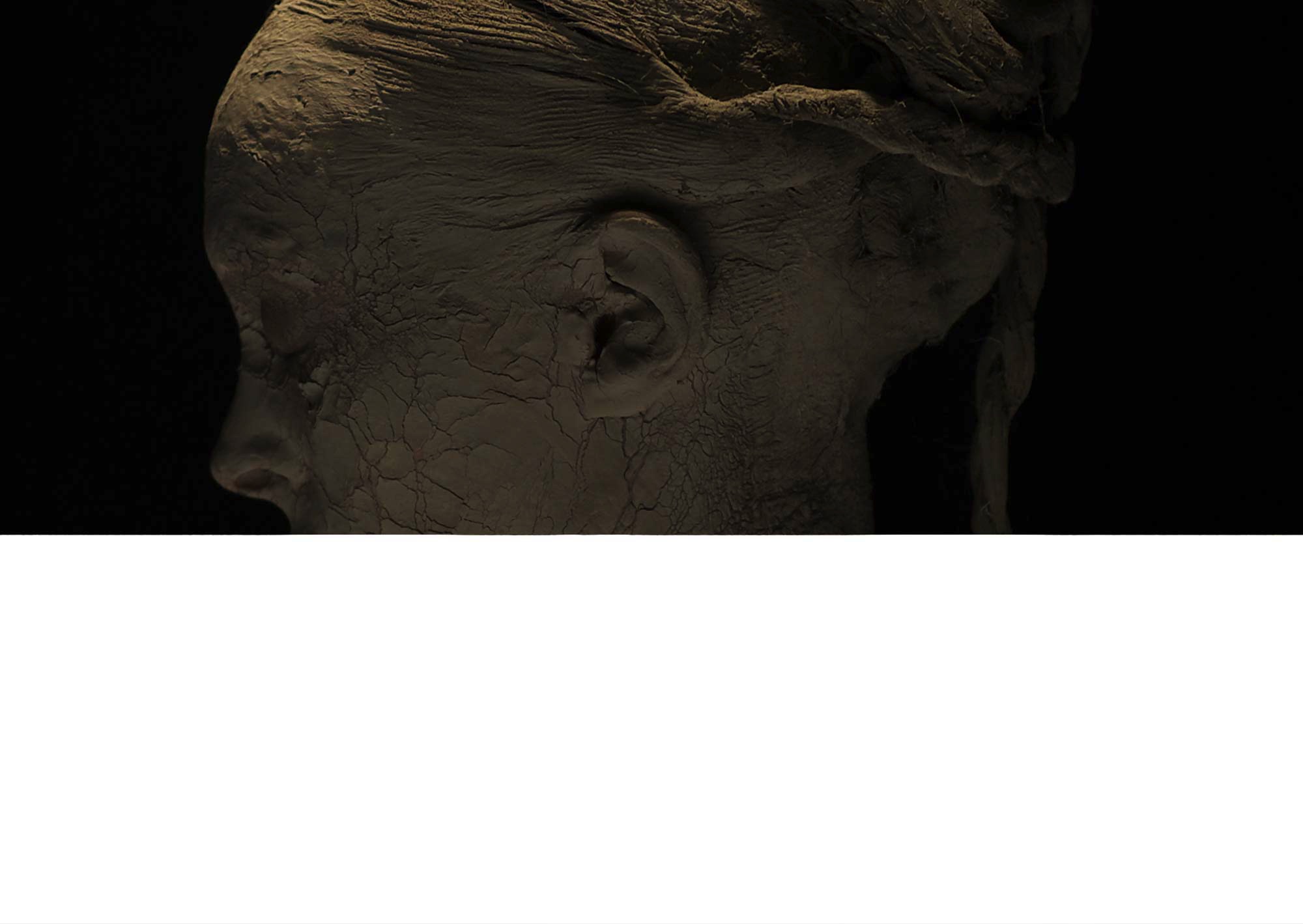

In Vault Over Cristina Gori fa qualcosa di simile e contrario. Parte dall’archeologia, dalla scoper- ta dell’esercito di terracotta dell’Imperatore Qin Shi Huang nella citta’ di Xi’an e, coprendosi con l’argilla, si trasforma in alcune figure chiave dell’armata formata da oltre 6.000 sculture. Lavora sui propri capelli, acconciandoli similmente alle sculture dei guerrieri, rivestendo così i vari ruo- li che queste significavano al tempo: dal soldato semplice al generale, all’Imperatore. Era forse un mondo romantico, un mondo in cui i ranghi venivano distinti in base alla pettinatura, ma era anche un tempo di guerra e di morte, in cui l’Imperatore, che fu il primo ad unificare il territorio cinese ed a sentire l’esigenza di proteggerlo iniziando la costruzione della Grande Muraglia, cerca di protegge- re anche se stesso: prima della morte, non dormendo mai nella stessa stanza per due volte di seguito e, dopo la morte, mettendo a guardia del suo mausoleo tutto il suo esercito, schierato. Un esercito di terracotta, ma riprodotto in maniera fedele in ogni particolare, con i tratti somatici di tutti i soldati. Visto da lontano, disposto com’era secondo uno schema di guerra, sarebbe sembrato un vero schieramento e avrebbe fatto desistere i nemici dal tentativo di arrivare fino alla sua tomba. Sem- brerebbe una leggenda, se i soldati di Qin Shi Huang non fossero stati ritrovati relativamente pochi anni fa, nel 1974. Oggi vengono subito in mente a tutti, parlando della Cina. E della Cina, oggi, si parla sempre.

VAULT OVER

La riflessione alla base del progetto Vault Over parte da uno dei paradossi più importanti che ci poniamo sulla storia e la continuità dei due grandi blocchi economici rappresentati dalla dicotomia Occidente / Oriente. Sempre più spesso sentiamo parlare di divisione tra il mondo West e il mondo East e allo stesso tempo di globalizzazione. Queste due idee completamente in contrasto tra di loro sono entrambe vere, dimostrate, studiate e sostenute. Si può dire che si tratta di uno dei grandi paradossi del nostro tempo, forse persino quello più importante. Ecco perchè molti artisti sentono il bisogno di indagare quale sia il limite di veridicità tra queste due tematiche. Quanto sono davvero distanti oppure uniti Occidente e Oriente?

Lavorando su queste riflessioni e su quello che sembra uno scontro tra due sistemi, Cristina Gori usa se stessa e l’elemento del suo corpo che sente come maggiormente contraddistintivo della propria

immagine : i suoi capelli, particolarmente lunghi , per creare un incontro tra le due culture, ed identificarsi con uno dei simboli più conosciuti e rappresentativi della storia della Cina: l’Esercito di Terracotta. Infatti, sono proprio le acconciature dei guerrieri a caratterizzare le va- rie posizioni all’interno dell’antico esercito cinese dell’imperatore Qin Shi Huang. Attraverso una serie di autoritratti Cristina Gori trasforma se stessa in una ibridazione tra l’identità veneziana e quella cinese, dando una personale visione della Via della Seta attraverso la sovrapposizione e la stratificazione delle due culture e delle loro storie. Coperta da uno strato di argilla l’artista si trasfigura e si immerge nella storia rivestita di una seconda pelle ricca di rimandi sociologici e storici, presentando un lavoro in un cui l’uomo e la sua umanità (messi in risalto dal fatto che ad essere rappresentato è non l’intero corpo ma la sola testa) diventano somma di un flusso vitale infinito e immortale che ha attraversato tutti i secoli, che ci compone e che ci sopravvive per continuare ad accumularsi e perpetuare la sua costruzione eterna del mondo.

In Vault Over, Cristina Gori compie un viaggio in cui sono presenti tutti questi aspetti, senza pero’ renderli espliciti poiché appunti introduttivi a un’epoca che l’artista vive e assorbe, ma dei quali non fa il soggetto vero e proprio del suo lavoro. Questo è, invece, qualcosa di molto più etereo e in qualche modo nobile. Senza farsi intaccare da considerazioni di mero pragmatismo, l’artista arriva al cuore delle cose, all’anima di un mondo indiviso, dove la distanza (nello spazio o nel tempo) è annul- lata in una onnipresenza storica e geografica che non spiega nessuna tesi in modo didascalico, ma vive in un simbolismo super partes. Si tratta di una sublimazione in cui sono ricongiunti il mondo occiden- tale e quello orientale, i conflitti e i loro punti di unione, in una metafora antica e poetica: quella della Via della Seta. E’ infatti proprio la Via della Seta che in antichità collegava la Cina a Vene- zia, città per la quale questo progetto è stato concepito e dove Cristina Gori ha studiato e vissuto. Tragitto tra i più importanti della storia per gli scambi commerciali e culturali, è proprio quello percorso e narrato da Marco Polo. Cristina Gori, sulle orme del mercante e viaggiatore veneziano, scrive il suo Milione personale, una sorta di autobiografia di una cultura ibrida che il mondo attuale sta costruendo o, più semplicemente, riconoscendo. Una storia che l’artista avverte come estremamente personale, ma che eppure rappresenta un lasso di epoche intere e di distese infinite. Il percorso che Marco Polo compie in un lunghissimo lasso di tempo, Cristina Gori lo puntualizza in un’unico momento, ripiega su se stessa tempo e spazio creando una stratificazione ardita, che riesce a portare a termine in modo delicato e sottile, forte per quanto misticamente silenzioso.

Un lavoro che potrebbe essere politico, riesce così a non esserlo, rifiutando di costruire un’arte di- dascalica come è purtroppo molta ricerca contemporanea e scegliendo, piuttosto, la strada della tra- scendenza. Perchè, se sotto la maschera di argilla che la ricopre e la trasforma ci sono motivazioni

sociologiche e antropologiche, se c’è tutta l’attenzione che viene data alla Cina anche per il suo inaspettato boom economico, se c’è dietro una riflessione sull’allontamento e avvicinamento tra due culture e sulla lama tagliente su cui si muovono gli equilibri mondiali, c’è però anche e soprattutto un lavoro di indentificazione: identificazione nella storia del mondo, nel suo plot storico, nel suo percorso fisico, un’ibridazione in cui il corpo dell’artista si trasforma in una trama squamata di ar- gilla che richiama ad un passato specifico ma anche generico e ancestrale, un immergersi nel rapporto dell’uomo con la natura, con una terrenità profonda, un attaccamento alla materia del mondo. Materia che in questo caso è sia l’argilla con cui Cristina Gori si ricopre, sia la seta che simboleggia la via commerciale tra gli antichi mondi, ma anche il materiale in sé stesso: una fibra pregiata e organica, che il baco costruisce come bozzolo, casa e incubratrice, avvolgendosici completamente.

Il libro di seta Steering Thread che fa parte del progetto, di dimensioni imponenti e dall’aspetto sognante, è il contenitore ideale e simbolico della fascinazione della storia cinese e dei suoi rap- porti con l’occidente, una storia che a volte sembra fin troppo fiabesca per poter essere creduta se non fosse stata provata. E’ anche il simbolo di una stratificazione, dello svolgersi delle cose, della storia che si percorre come lo scorrere delle pagine di un romanzo. E ancora, è un libro bozzolo, un libro casa, un libro incubatrice, in cui la natura del mondo – possiamo immaginare - si crea e cresce. Del resto, così come il baco utilizza i filamenti di seta che ripiega attorno a sé avvolgendosici, così Cristina Gori usa i propri capelli, particolarmente lunghi e lasciati crescere con pazienza negli anni, ripiegandoli su se stessi fino a creare le acconciature che identificavano l’esercito di terracotta. Diventa soggetto embrionale di una storia che, essendo infinita, è anche potenzialmente sempre neonata, sempre sull’orlo di una crescita nuova. Costruendosi come creatura inedita, fusione tra culture, tempi e luoghi, l’artista diventa un nuovo essere vivente che non ha necessariamente caratteristiche umane, nonostante ne abbia il vago aspetto. E’, infatti, soprattutto scultura organica costituitasi tramite un sentito, lungo, laborioso e, a volte, doloroso intervento performativo in cui l’artista si astrae metodicamente e accuratamente nel passato cinese.

Il corpo e la trasformazione del corpo è spesso utilizzato nell’arte del Novecento per parlare di si- tuazioni molto più vaste, soprattutto sociali e politiche, ma anche – come nel caso di Cristina Gori - storiche o legate a condizioni del mondo che possono persino trascendere l’elemento umano vero e proprio. In questo processo hanno avuto forza soprattutto le artiste donne degli ultimi decenni che, anche grazie una nuova idea di libertà femminile, sono riuscite a trasformarsi di caso in caso in idee e in metafore viventi con maggiore carica emotiva e simbolica. Dalle performance di Marina Abramović agli autoritratti concettuali di Cindy Sherman, abbiamo visto degli esseri umani stravolgersi in

maniera drammatica oppure ironica, allargandosi fino a diventare concetto. E’ proprio su questa dire- zione che lavora anche Cristina Gori, con un lavoro impegnato e delicato allo stesso tempo in cui usa la sua forza personale per diventare una posizione che va oltre se stessa. Creando sulla propria testa le elaborate acconciature dell’esercito di terracotta, ricorda i body-extension piece di Roni Horn, in particolare Unicorn, mentre il suo nascondersi nella terracotta per trasformarsi in scultura è un processo non troppo lontano dalle azioni di Carolee Schneemann che si copriva di vari materiali per fare di se stessa un oggetto d’arte che la spersonalizzasse.

E’ proprio sull’idea di pelle di natura, come superficie tattile ed ideologica , che l’artista basa la propria ricerca artistica incentrata sul dualismo natura - artificio , sul concetto di imitazione ed ibridazione tra due elementi in antitesi. Per esempio, la serie fotografica Mimesis verte sull’ inte- razione tra natura e corpo e ricerca la fusione tra i due elementi naturali attraverso la proiezione diretta sulla pelle di tronchi, rami, al fine di ottenere un risultato innaturale, artificiale. Mimesi come imitazione, fusione tra natura e corpo in cui il corpo ne assume la pigmentazione, la indossa come una seconda pelle, artificiale e naturale allo stesso tempo, si fonde con essa. Mentre nella serie fotografica Metamorfosi interviene tramite disegno digitale per creare una sorta di natura artificiale, dal colore verde fluorescente, che si va ad ibridare al corpo ed a fondersi con esso in un processo metamorfico, di modificazione.

Viene naturale chiedersi quale posizione assuma l’artista rispetto all’unione delle due culture che impersonifica in quest’ultimo lavoro. Ritorniamo quindi alla domanda iniziale posta da questo testo: quanto è reale la divisione o l’unione tra Occidente e Oriente, qui rappresentati da Venezia e Cina, i due capi opposti della Via della Seta? Quanto è possibile che questi convivano in una figura unica? L’embrione dell’uomo figlio della storia, che eredita le due culture e trascende le distanze del mondo, è più morta scultura dagli occhi chiusi, immobile e gelido sotto un’argilla indurita, o è più baco che cresce al riparo nella seta pregiata? A rispondere è un segno. La figura dell’Imperatore, per forza di cose più importante, più evidente, per forza di cose punto di arrivo, è l’unica in cui Cristina Gori si autoritrae con gli occhi spalancati, guardando in modo fisso lo spettatore, instaurando un dialogo e rendendo quindi la rappresentazione viva, attiva e partecipata. Dopo la gestazione di un percorso di sculture che sembrano preparatorie, arriva il simbolo vero e proprio dell’incontro, imperatore per una questione di citazione storica, ma che in realtà è più che altro una figura traslata in cui si realizza l’unione tra la materia del mondo, tra le storie e le geografie, tra Venezia e la Cina, tra il vicino e il lontano, tra il presente e il passato, in una visione ampia, aperta come gli occhi dell’artista, puntati in una direzione frontale che ci trapassa.

Carolina Lio

INTRODUCTION

Through the centuries the world has changed. The history, as such, is passed and in some sense lost. But anyone really involved in history does not like to say that the past is lost, but that is bu- ried in the less gloomy sense of the term: just covered. The world changes, indeed, but it is not really transformed. His is a work of overlapping and layering. The world grows older and while he is growing, it is covered by something new. In this project, Cristina Gori does something both similar and opposite. She starts from archeology, by the discovery of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Terracotta Army and, completely covered by a layer of clay, she transformes herself into some of the more than 6,000 found sculptures. She works mainly on her own hair, combed it in the same manner of the various sculptures and covering so the most roles that they meant, from the simple soldier to the general, to the Emperor himself. Perhaps, it was a romantic world, a world in which the ranks were distinguished on the basis of the hairdo, but it was also a time of war and death, in which the Emperor, the first who have unified the Chinese territory, feels the need to protect it starting the construction of the Great Wall. He seeks to protect himself too: before his death, never sleeping in the same room for two times consecutively and, after his death, making his mausoleum guarded by all his army, deployed. An army made of terracotta, but perfect in every detail, with the features of all the soldiers accurately reproduced. Seen from far away, in a pattern of war as it was arranged, it would have seemed a real deployment and the enemy would been discouraged from trying to get to the Emperor’s tomb. It would seem a legend if Qin Shi Huang’s soldiers were not found relatively few years ago, in 1974. Today they come readily to everybody mind, talking about China. And today we always talk about China.

VAULT OVER

The thought behind the project Vault Over starts from one of the most important questions we ask ourselves about the history and the continuity of the two major economic blocs represented by the dichotomy West/East. More and more often we hear talking about the division between these two worlds and, at the same time, of globalization. These two ideas, completely at odds with each other, are both true, demonstrated, developed and supported. We can say that this is one of the greatest paradoxes of our time, perhaps even the most important. This is why many artists feel the need to investigate what is the limit of accuracy between these two issues. How very far apart or joined are East and West? Working on these considerations and on what feels like a clash between two systems, Cristina Gori uses herself, her image and the element of her body that feels like more distinguished, her especially long hair, to create a meeting between the two cultures, and identify herself with one of the most popular and representative symbols of China’s history: the Terracotta Army. Covered by a layer of clay, the artist transfigures and immerses herself in the history, coated with a second skin rich of sociologi- cal and historical references.

She presents a work in which the man and his humanity (highlighted by the fact that to be represented is not the whole body, but only the head) becomes the sum of an infinite and immortal flow of life that has passed through the centuries, that made us up and then survive us to continue to accumulate and perpetuate its eternal construction of the world.

Without being affected by practical considerations, the artist gets to the heart of things, the soul of an undivided world, where the distance (in space or time) is withdrawn in a historical and geographi- cal omnipresence that does not explain didactic thesis but, on the contrary, lives in a non-partisan symbolism. It is a kind of sublimation in which West and East, with their conflicts and their points of union, are rejoined in an ancient and poetic metaphor: the Silk Road. And it is the Silk Road, indeed, that in ancient times linked China to Venice, city for which this project was conceived and where Cristina Gori studied and lived. Route among the most important in the history for trade and cultural exchanges, it is the one followed and narrated by Marco Polo. Cristina Gori, in the footsteps of the venetian merchant and traveler, writes her personal Milione, a sort of autobiography of an hybrid culture that the nowadays world is building or, more simply, recognizing. A story the artist felt as very personal, nevertheless it is a period of entire epochs and thousand of kilometers. The route that Marco Polo made in extension, is pointed out in one single event by her, who folds back on itself time and space, creating an audacious stratification that manages to carry out in such a deli- cate and subtle, strong as mystically silent way.

So, a work that could be political, manages not to be, by refusing to build a didascalic art such as it is unfortunately much contemporary research and, rather, by choosing the path of transcendence. Because, if under the clay mask that covers and transforms the artist there are sociological and an- thropological reasons, if there is all the attention that is given to China for its unexpected econo- mic boom, if there is a reflection on estrangement and rapprochement between the two cultures and the sharp blade where the world balance is moving, there is also, and above all, a work of identifications: identification in the history of the world, in its historical plot, in its physical path, an hybridi- zation in which the artist’s body turns into a flaky texture of clay which has reference to a specific past but also to generic and ancestral one, a plunge into the relationship between man and nature, with a deep attachment to the matter of the world. The matter, in this case, is both the clay with which Cristina Gori is covered, and the silk that symbolizes the ancient trade route between worlds, beyond the material in itself: a precious and organic fiber, that the silk worm constructed as home, cocoon and incubator, completely sheltering itself.

The book made of silk Steering Thread, part of the project, has a massive proportions, looks like dreamy and is the ideal and symbolic container of the Chinese history fascination and its relations with the West: a story that sometimes seems too fairytale to be believed if it were not been proven. It is also the symbol of a stratification, of the unfolding of things, of the history that runs like the flow of the pages in a novel. Still, it is a book cocoon, a book house, a book incubator, where the nature of the world - we can imagine - is created and grows. Moreover, as the silk worm uses strands of silk turning them all around itself, so Cristina Gori uses her hair, particularly long and pa- tiently allowed to grow over the years, bowing back in order to create the hairstyles that identified the Terracotta Army. She becomes the subject of an embryonic history, infinite and so also potentially always baby, always on the verge of a new growth. Built up as an unprecedented creature, fusion of cultures, times and places, Cristina Gori becomes a new living being that should not necessarily have human features, even though she has a human vague appearance. It is, in fact, especially an organic sculpture constituted by a heartfelt, long, laborious and sometimes painful performative intervention in which the artist methodically and thoroughly abstracts herself in the past of China.

The body and the transformation of the body are often used in the art of the twentieth century to talk about situations much wider, especially social and political, but also - as in the case of Cristina Gori - historical or related to conditions that can even transcend the human element itself. In this process, the female artists of recent decades had a special strength thanks to a new idea of female freedom that allowed them to turn themselves in ideas and in living metaphors with more emotional and symbolic energies. From Marina Abramovič’s perfomances to the conceptual portraits by Cindy Sherman, we saw human beings ironic or dramatically twisted, expanded to become a concept. It is just this di- rection the one taken by Cristina Gori, with a committed and delicate work where, using her personal power, she becomes a position that goes beyond herself. Creating on her head elaborate hairstyles of the Terracotta Army, she recalls the body-extension pieces by Roni Horn, in particular Unicorn, while her hiding in the clay in order to become sculpture is a process not too far from Carolee Sch- neemann’s actions in which she was covered with various materials to make herself a depersonalized work of art.

Cristina Gori has always focused her research on the idea of the skin of nature as tactile and ide- ological surface, exploring the dualism between natural-artificial and the concept of imitation and hybridization between two elements in opposition. For example, the series Mimesis belongs to a path of photographic research which deals with the interaction between nature and body through the direct

projection onto the skin of trunks, leaves and branches. Mimesis as imitation, merging between nature and the body which wears it as a second skin, natural and artificial at the same time. Moreover, on the photographic series Metamorfosis she draws with digital pen a sort of artificial nature, green fluore- scent color, which hybridizes the body and becomes part of it in a sort of metamorphic process.It is natural to ask ourselves what position the artist takes over the union of the couple of clashing cultures that she embodies in her latter work. Then, let us return to the original question posed by this text: what is the real division or union between East and West, here represented by Venice and China as the two opposite ends of the Silk Road? How can they live together in a single figure? The human embryo son of history, which inherits the two cultures and transcends distances in the world, is it more a dead sculpture with closed eyes, still and cold under the hardened clay, or is it more a silk worm that grows sheltered in fine silk? The answer is given by a sign. The figure of the Emperor, necessarily more relevant, more evident, the inevitably ending point, is the only one in which Cristi- na Gori has got wide open eyes, looking at the viewer in a fixed way, initiating a dialogue and thus making the representation alive, active and participative. After the gestation of a path of sculptures that seem to be the preparatory, it comes the true symbol of the encounter, emperor just for a matter of historical mention, but which is, actually, more than ever, a translated figure in which there is the union between the matter of the world, between histories and geographies, between Venice and Chi- na, between the near and the far, between the present and the past, in a broad view, as open as the artist’s eyes, pointed in a forward direction that passes through us.

Carolina Lio